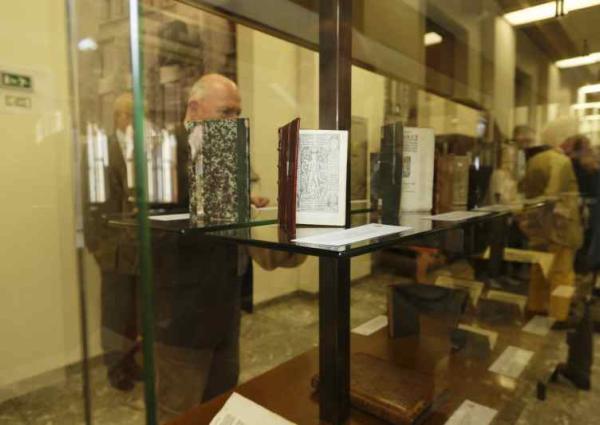

Book presentation: Le goût de la bibliophilie nationale

back to the overview

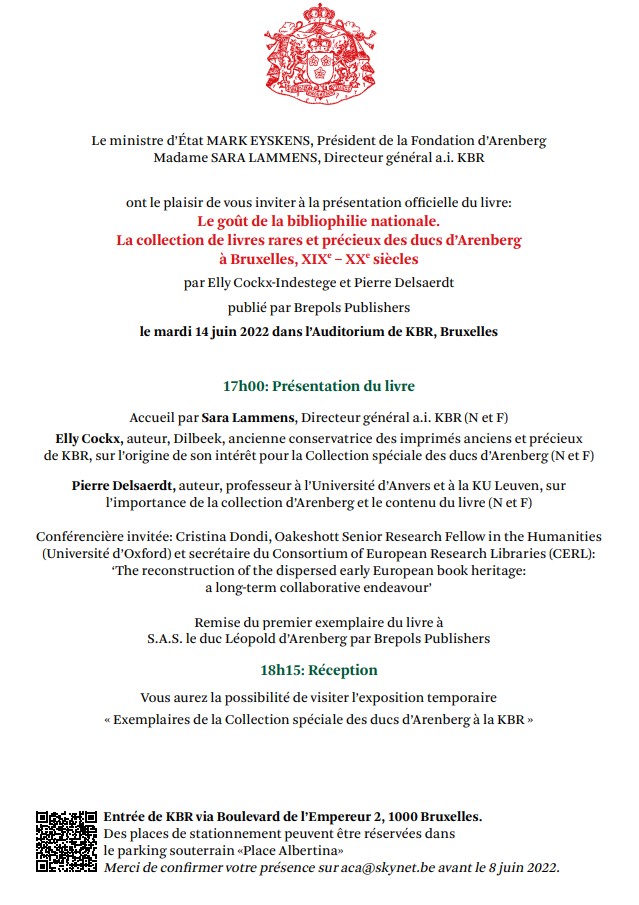

Book presentation on Tuesday, the 14th of June at 5 pm, KBR Bruxelles

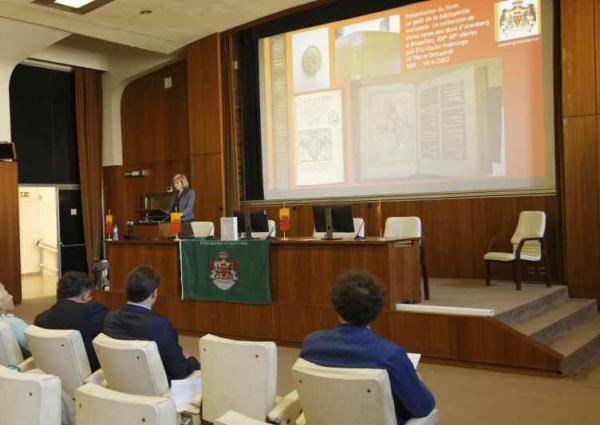

Speech by Cristina Dondi, OSI, Professor of Early European Book Heritage, University of Oxford

The reconstruction of the dispersed early European book heritage: a long-term collaborative endeavour

The book is by nature a mobile object, but during the classical and medieval period its circulation is relatively limited. Manuscripts, even those produced serially for universities, tended to be used, and to remain, within the area in which they were produced. It is with the advent of printing that mobility becomes an essential component of the new commercial enterprise, decisive for its success: printers soon understand the need to find a market for the hundreds of copies produced for each edition, a market which extends well beyond their place of production.

The new commercial activity was tested in 262 European cities, with different levels of success. Venice, the largest printing and exporting city in 15th-century Europe, counted 250 printing shops.

The success of printing is primarily due to a simple market factor: the demand factor. In the fifteenth century, an ever increasing production of handwritten books was the effect of the demand for more and more books, of all kinds_ prices_and_workmanship, but at the same time it was also the cause of experimentation with the mechanical means of reproduction and its success. Behind this there is, however, an eminently cultural factor: the predilection of European civilization for the written text ̶̶- a widespread predilection, highlighted by the growth of literacy and the value placed on knowledge, its training and diffusion. Values that in the fifteenth century are certainly not limited to the centres of secular or ecclesiastical power, but are indeed well rooted among professionals and, in parts of Europe with flourishing trade activities, labourers of various kinds.

Printing responds to, and accelerates, this widespread demand, from below, and it is important to underline how printing in Europe is an eminently commercial phenomenon, which did not fulfil only the needs of the Church, scholarship, and university, but also much wider and diverse sectors of the population and institutions. If it had remained an elite phenomenon, it would have existed in parallel with a more backward society. But now we know that printing pervaded the whole of society. We know this from the data that we have been collecting over the years, from the thousands of books that we are examining, from the prices of the books which we are now sharing, from the typological analysis of all the editions of the fifteenth century, which is finally offering a comprehensive view.

By 1500 Europe was awash with millions of printed books. As printing continues in the following centuries, many of these early specimens are destroyed as obsolete, replaced by newer editions and new genres. But many also found their place in libraries. And here I pass from distribution to survival.

From the sixteenth century onwards, vast quantities of these early printed books have been displaced and partly destroyed. Evidence exists in very large quantities to support the relation between specific major European political events, and the sequestration, disposal, transfer, and sale of book heritage, beginning with the secularizations of the religious houses of Europe which were implemented under Henry VIII, Joseph II, Napoleon, the Spanish desamortización, and the formation of the Italian State. We can hardly find a library in Europe today which has been unaffected by these historical events. Our libraries are built up like mosaics from shards of earlier libraries. Books move into and out of libraries for a wide variety of reasons, our early European book heritage is scattered, and a substantial portion of it has migrated to the United States. Years of research on the history of books and libraries indicate that overarching factors have determined the present configuration, first and foremost, major political changes.

The connection between political change and the migration of book heritage was first systematically investigated, in its diachronic and Europe-wide dimension, in a 2012 Oxford conference which I organised together with my dear colleague in Oxford Richard Sharpe and Dorit Raines, from the University of Venice Ca’ Foscari.

In his brilliantly incisive paper on ‘Dissolution and dispersion in sixteenth-century England: understanding the remains’, Richard perceptively observed that the almost complete destruction of British monastic book collections is a strong reminder of what happened when technological change and political change overlapped. Never again in European history did these destabilising factors collide so explosively. In 16th-century England, most of the manuscripts and printed books from closed down monasteries were simply destroyed; antiquarianism and collecting, which forged the idea of heritage, were not yet developed.

But the aftermaths of the Reformation on the Continent, the Thirty Years War, the French Revolution, the national dissolutions of religious houses by liberal governments, the October Revolution, and the two World Wars have certainly led to more partial destructions and dispersals of book collections. And the dispersals have been massive. We can hardly find a library in Europe today which has been unaffected by these historical events, whether negatively, because it got dispersed, or positively, because it was formed by, or grew with, those remains. The final step of the migration of the books to the US could only be sketched out because of the lack of evidence, but in these last ten years we have been working more closely with our American colleagues to remedy that. The emerging evidence is linking the availability of rare books material on the international market, material which was eventually acquired in the United States thanks to its growing economic power in the last century, to specific major European political events which shook a system of knowledge preservation that had been in place for centuries.

It would be difficult to explain the cultural significance of the Grand Tour for the formation of the most important British and French cultural institutions without the secularizations of the Napoleonic period, which facilitated the displacement, removal, and sale of large quantities of European artistic and book heritage. Or the similar formation of the largest American collections, without the second wave of Italian secularizations at the dawn of the formation of the national state (1861). In both historical periods, more or less institutionalized spoliations accompanied the disintegration, perhaps physiological, of large aristocratic collections.

By defining and quantifying the connection between major European political changes and the displacement of cultural heritage – specifically, books and libraries – using a bottom-up approach from the books themselves, we can finally match historical events_and_policies with the actual consequences, intended and unintended, direct and indirect, of those political actions.

The results of this research are timely, as we interrogate ourselves on the impact of technological change on our evolving society, in a highly volatile political landscape and impending economic retrenchment. The findings will spell out the devastating effects of the policies of the past, as well as the extensive, expensive, and time-consuming efforts which are necessary today to piece collections back together. The dividends for scholars in Europe and internationally working on intellectual history are immense. But this picture, and these data, are also necessary for libraries and governments grappling today with the ongoing process of knowledge_and_books preservation and disposal brought about by the digital shift.

It is this cultural complexity, and mobility, that an international project such as Material Evidence in Incunabula (MEI) manages to capture, in collaboration with libraries, custodians of the heritage, and scholars from the university and library world specialized in its study, supported by an advanced digital eco-system, created and maintained by CERL, which offers not only shared cataloguing but also the possibility of integrated research. Let me show you how we do it. [slides 12-27 until statistics]

We are now in the position to be able to trace and visualize the movement of thousands of books in space and time, and the formation and dispersal of book collections, to understand the ways in which the first printed books were used and survived (or were lost) and to understand long-term trends in the acquisition of books and the formation of collections.

The concept of provenance is at the core of this research. Provenance does not only pertain to our immediate past. A number of heritage institutions seems to associate it with colonization and Nazi loot. Provenance pertains to the entire life of an object, from the moment it is created - for a printed book, the time of printing - to that when it enters the current holding institution or ownership.

With Material Evidence in Incunabula we are in the process of reconstructing some 25,000 book collections. Every time I deliver a lecture in Europe or the United States, I access the database for a focus on a former collection, a city, or a country. In particular, I care to highlight those, often many, books which are no longer in the same city or country today, but are located in totally unexpected libraries around the world. A scholar, even a team of them, would never be able to locate them, but because these libraries are cataloguing their incunabula in MEI, this valuable information comes to us.

A search for ‘Belgium’ results in 263 hits.

For the 2012 Oxford conference on secularization, whose volume will be published imminently withing the same Bibliologia series, I singled out all the books from religious institutions which eventually entered the collection: 1352 books from 558 different religious houses. 92 books from 51 Belgian houses.

I did the same for the incunabula today in Harvard: 636 books from 348 different religious institutions. 10 books from 10 different Belgian houses.

Among the 263 Belgian collections listed in MEI, are 10 incunables today in San Daniele del Friuli (!), north-eastern Italy, formerly owned by the Flemish professor of Mathematic Adriaan van Roomen (1561-1615), who taught Medicine and Mathematic at the University of Louvain until 1592. After obtaining a second Medicine degree from the University of Bologna, he held the Chair of Medicine at the University of Würzburg.

But of course there is a strong presence of books from religious institutions:

Books from the Cistercian Monastery of Saint-Remy, Rochefort, Belgium are today at the Laskaridis F. of Athens (https://data.cerl.org/mei/02121656)

Tournai, Jesuit College > Athens, British School at Athens (https://data.cerl.org/mei/00201522)

Ninove, Premonstratensian, Sint-Cornelius en Sint-Cyprianus, O.Praem. > today Liverpool UL (https://data.cerl.org/mei/02133098)

Franciscans monastery of Courtrai or the Carmelites of Ghent > today London Lambeth Palace

https://data.cerl.org/mei/02010099

https://data.cerl.org/mei/02011899

https://data.cerl.org/mei/02011915

Franciscan Recollects Bruges, today Canterbury Cathedral Library

https://data.cerl.org/mei/02014654

Louvain, Charterhouse of Sainte Marie Madeleine sous la Croix, O.Cart. Today in Milan NL (https://data.cerl.org/mei/02019474)

Louvain, Franciscans (Recollects), OFM Recoll. > one Eton, one Princeton

Liège, Franciscans, OFM > today San Marino California, via English collector John Eliot Hodgkin and the German bookseller Otto Vollbeher

https://data.cerl.org/mei/02123097

The Arenberg collection figures with 31 records, today in Oxford Bodleian (14), Princeton (9), Harvard (5), The Hague KB (2), Cambridge UL (1).

But many more we will add from this magnificent publication, thanks to a CERL internship grant which has been assigned to create MEI records from the incunabula in this Arenberg catalogue. This will facilitate the identification of the many volumes from this collection which today are still unlocated, out there in some libraries.

These disiecta membra of Belgian collections scattered around the world, which I have so easily listed, conceal a difficult and long process of identification, based on palaeographic, bibliographic and librarianship competence. And a long collaborative work, carried out by hundreds of people in hundreds of libraries. There is an enormous work to be done to trace the survival and understand the dispersal of our book heritage. The data on Belgian incunabula still in Belgium today, which cataloguing projects are opening up to all of us, should enter MEI to recompose the heritage that History has divided over the centuries. Being able to map and quantify the older Belgian book heritage in the world is not only an opportunity to study, to understand more in depth the use and ownership of books in today’s Belgium. It is also a necessity, to enhance their significance, to highlight the extraordinary relationships that bind us today to many cultural institutions around the world, and to build on these bonds shared_research_and_enhancement projects. I refer here also to the sharing of the cost of the investments, in competence, time, and money, necessary for the study of our shared book heritage. y

The European printing shops physically produced and distributed education and knowledge throughout the Continent; with perspicacity the Financial Times has titled an article on the research of the ERC 15cBOOKTRADE, project which I led, ‘The birth of the knowledge economy’.(1)

The impact of early printing has been not only cultural, but social, political, and economic, in a past that closely resembles our present.

The European book collections scattered throughout the world are ambassadors not only of what was collected on the continent, but also of the value that other countries have always attributed to the European book. Mapping, quantifying and studying the dispersal, and pervasiveness, of the European book around the world will help those who work with books and libraries in Europe to explain what hand-written and printed books signify today for our civilization in full digital flow.

But let me spell it out clearly again: this vital recovery of our scattered heritage can ONLY be done collectively. Thank you.

(1) The Financial Times, “Birth of the knowledge economy”, 9 January 2018, by James Pickford

Related

In this volume, Mrs. Elly Cockx and Professor Pierre Delsaerdt present the results of their…

read more >